|

jottings |

JOTTINGS FROM A SALESIAN TRANSLATOR

There is no particular order to these, and no particular originality either! Translators are not supposed to be too original! You will find these thoughts already expressed by well-known translators, especially on translator forums—or you may find them inside your own head if you have done a bit of translation yourself. They are not complete—this is clearly a work under construction, forever!

|

1 |

▲back to top |

|

1.1 Compromise |

▲back to top |

Even a very good translation is the result of a compromise. The linguistic capabilities of any two language sets are never equivalent: exact meanings, aesthetic qualities of words may have no reciprocal match. For example the Italian word nipote has six different meanings: grandson, granddaughter, brother’s son, sister’s son, brother’s daughter, sister’s daughter.

Beware! Since grammatical structures differ, it is almost certain that traits of the original (let’s call it the prototext) will appear in the translation (let’s call it the metatext).

In other words, the influence of a Salesian Italian original, if that is what we are dealing with, will almost inevitably be evident in the translation: clumsy constructs borrowed, absence of some of the marvels of Italian expressiveness in the translation! But it will be just as true of any language pair.

|

1.2 ‘Standard forms’ |

▲back to top |

We all learn to write in certain ways, according to certain standard forms, and we cannot easily unlearn these. The author, whoever he or she is, of the text we are translating did this too. Don Bosco even discusses, in certain places, some of his ‘standard’ forms, for better or for worse (writing homilies cf. MO, writing letters, cf ‘Salesian Sources’). The difference between his standard forms and mine is part of the problem of translation. I may impose my view of life, not his, in my choice of style, lexical alternatives, interpretation of ‘likely’ meaning—or what is worse, I may simply not be aware of what his standard forms were in the first place.

In fact, this point about standard forms is even historically interesting for us. Napoleon invaded Italy in 1850. Ironically, he propelled the Italian language towards its standard form. Interestingly, this French invasion inspired patriotism within Italians. Not only were they incited to unify their country, but they also started taking pride in the standard Italian and made it their official language. This solidified the shift in focus from regional dialects to standard Italian, especially evident in Don Bosco’s case as he insisted on the use of Italian rather than Piedmontese at Valdocco.

|

1.3 Dominoes |

▲back to top |

Every choice has repercussions, like a falling domino sets off a chain reaction. Der Gute Mensch. Is it male or female? I mean, not grammatically, but really! Bertold Brecht wrote a play about ‘der gute mensch’ of Sezchuan. In German you can do that. In English, mensch comes down, not to ‘mankind’ or ‘person’ but to either a man or a woman, and whichever you choose you are stuck with the consequences (pronouns, for example). It turns out to be a woman!

|

1.4 Loss |

▲back to top |

Every act of communication can experience loss: grammar, meaning, interruptions, misunderstandings, ‘noise’ … Translation is a form of communication particularly open to loss, so let’s accept it.

If the text is from the past, you may want/need to modernise it. That too, is loss. Or maybe the genre doesn’t exist in my culture.

If translation is in some respects a copy, that too is loss. It would be arrogant of me to suggest that my translation is better than the original. But there is an exception! Authenticated translations (e.g. of the Constitutions) are just as inviolate as the originals, hence in some respects are not translations at all—for many if not most of their readers, they become ‘the original’. That is some responsibility!

|

1.5 Do translators ‘age’ more quickly? |

▲back to top |

I really mean their translations of course. And yes, they ‘age’. Let’s face it, as soon as you translate something, someone will want to fix it, improve it! Yours then becomes dated. Why?

It follows, really. The original tends to be more stable in time. In fact it ‘freezes’ things in a moment of time in a culture, and unless the author rewrites it, that is how it stays. But the translator is writing for another time or for a time tied to another culture. His (or hers) is a ‘version’, and there will be more versions, probably.

In fact it is not the translators or translations who are ageing but the readers! That’s why we need new versions.

|

1.6 How many texts? |

▲back to top |

Maybe there are three or four texts involved in any translation:

A. The original, the prototext

B. Me, the ‘protoreader’ as I do my analysis, my pre-prep translation-orientation with all its possibilities, the additional texts I may be consulting, the ideas in my head …

C. My choices as a translator, my ultimate ‘version’.

D. The reader of my translation.

No wonder this is a complicated game!

|

1.7 Climbing the culture wall |

▲back to top |

There is a wall between any two cultures —don’t let people deny that. But the translator has to climb that wall, or go up it!

As I peek across the wall I may be tempted to explain what I see on the other side, rather than just describe it or ‘carry it across’ the wall (if we subscribe to the literal metaphor of trans-late):

- an extra word or two here and there

- a translator’s note

- a footnote

- an afterword

I am expanding the text. Can I do that?

|

1.8 Is anything ‘untranslateable’? |

▲back to top |

Surely not, as difficult as it may seem. To admit so may say things about languages or cultures that we do not want to believe. Only what can’t be shared can’t be translated, and human beings can share anything. It just means you have to be very, very clever sometimes.

Sometimes “untranslatable” just means something you haven't thought about hard enough. Italians just love making up words or playing with words, so we get: Qualunquismo—Apathy and indifference towards politics. Sciupato is quite a visual Italian word that's hard to convey with one word in English—it means everything from having the blahs, to looking pale, to feeling not that good. Solo means ‘only’ or ‘alone’. A solo by a singer is un assolo, and that’s not being rude! A solo singer is un solista.

Authors will play with words. Can you translate a pun? Look at it this way; wordplay on the author’s part is an invitation to play. So play! I had a case recently where an Italian speaker was playing with words, calling himself 'mai-a-letto'. He was suggesting a play on words with two possibly meanings, one, that he was a busy man who never took a rest, two, that he might be a little pig! These kinds of puns don't easily translate into other languages, so my solution was to turn it into an email address: mai@letto. It's not the same thing of course, but it does make the point that if the author can play with words, so can the translator! Of course, this can work in writing, but rarely can you do this in interpretation viva voce: no time, no inspiration, the brain can’t handle all the intricacies of language when it’s speeding down a parallel track with the speaker, or the challenge just doesn't work in speech, where it might work in writing. And then ‘parallel’ is a misnomer. You should at least be intersecting occasionally, but chances are you may reach a point where you are poles apart.

Abrazo

Spanish is a demonstrative language, or should we say that hispanics are demonstrative people! They love to conclude a letter with 'abrazo', 'abrazo fuerte', 'cariño', terms like that. Nor is it uncommon for this to appear in maybe not the first but the second letter in a series of business-level exchanges. But we don't do that sort of thing in English, and even less so when its a male-female business relationship. So how do we translate 'abrazo' in English? Not with 'a big hug' or 'tight embrace' I would suggest! Try something like 'Fond regards'.

Buonismo – and other neologisms

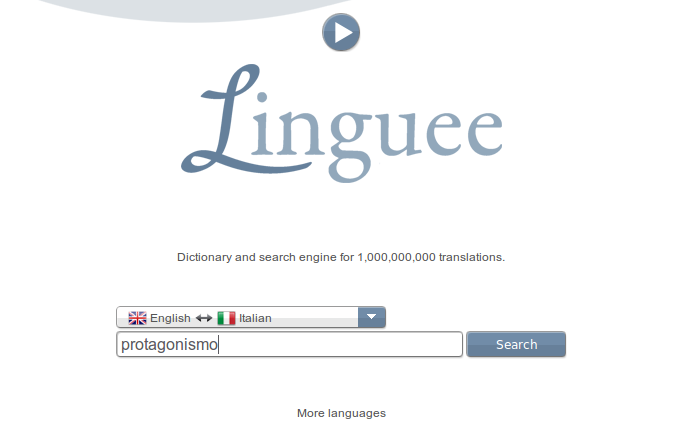

Italian is a morphologically productive language, especially -ismo! You can add it to almost anything. So no need for surprise when we find words like buonismo, alarmismo … Surprise no, but how do we translate them? This is where a site like Linguee is very useful, since it gives us aligned corpora of language pairs (e.g. it-en) and you will see various efforts at translating these kinds of words. In the case of buonismo, we might have a choice of:

Overly

sympathetic

Bleeding heart

Sentimental

Indulgent

Do

gooder

Good Scout

Sympathizer

Soft / Softy

Social

relativism

Triangulation

Centrism

Secular progressive

But all depending on context, please!

As for alarmismo, how about scaremongering?

|

1.9 Marked text |

▲back to top |

In linguistics we often refer to ‘marking’, meaning that something stands out for some reason: syntax altered from the normal, special word use, a metaphor or phrase slightly changed …

But in translation we have to consider that most texts are ‘marked’ in some way and recognising how they are is part of the challenge. It is not good enough to say ‘Italian is different from English.’ The translator has to be clear about how it is.

Metaphors and stock phrases are very likely candidates: other languages may share similar but not quite the same ideas and may do so in similar or even very different words.

Take this for example:

To thank one’s lucky stars (en)

Nascere sotto la buona stella (it: similar idea, similar equivalent terms)

Essere nato con la camicia (it: similar idea, totally different terms!)

Or consider that I put myself in another’s shoes, but my Italian friend will put himself in another’s clothes.

|

1.10 Oral or written |

▲back to top |

Just occasionally I have to determine whether to lean more towards the oral than the written, or literary text. Sometimes a text that was in fact oral masquerades as written. Off-the-cuff ‘a braccio’ stuff (Superior Generals, Popes often do this!) arrives on your desk as written text, and the temptation is to treat it as such.

Then you have different text formats occasionally to translate: subtitling, voice-overs, and most difficult of all, dubbing, since this includes the skill of assimilating language to lip movement inasmuch as it is possible to minimise the unavoidable ‘foreignness’.

|

1.11 Documenting |

▲back to top |

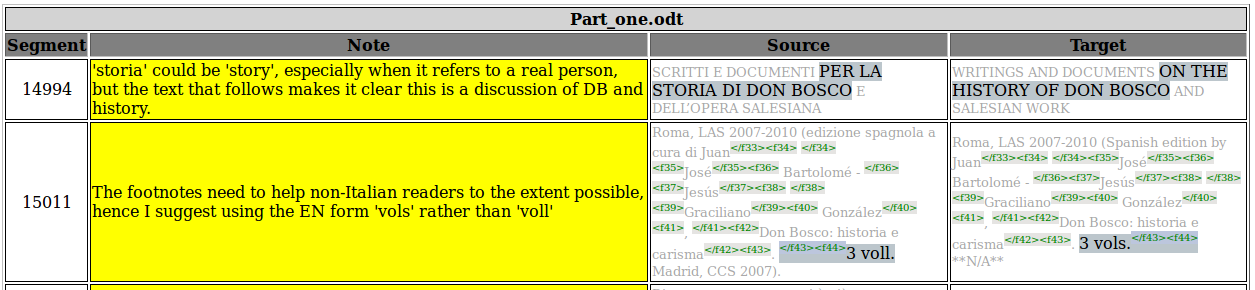

Do good translators document their efforts? If they have time and if the item warrants it, they probably do. I documented my entire effort to translate the new Youth Ministry Framework, so that the YM Councillor could actually know why I made certain choices and not others, and could feel free to adjust them if he wanted to.

But for this documentation to be truly useful, it will need to be done more formally. The options are there: OmegaT allows one to include notes on any segment. A script then permits one to convert these notes, as well as the original and translated segment they refer to, to html. That may be sufficient, since translators could easily share such html files.

If we wished to take this to a much more academic level, the html file could be converted to xhtml and thence to the TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) xml format.

|

1.12 Sector language |

▲back to top |

I mean this in the more general sense, that Salesian language is a ‘sector’ language with differences from ordinary language. And of course within this sector there are other sub-sectors (like Youth Ministry). Here there is a similarity with technical or scientific language. This is why we need to work on terminology, which comes to the fore in sector language.

When a charism (let’s call it a ‘sector’ though, for the purposes of this comment) goes worldwide, it needs a certain consistency of language. In contrast to normal etymological processes, ‘sector language’ has terms whose etymology is short. Terms are ‘invented’ sometimes by a Superior General, at other times by a General Chapter. Take ‘the grace of unity’ for example. The words, even the expression itself, may in fact have been born outside the Congregation, but we can date its adoption inside the Congregation by a given Rector Major (just as we can date ‘new evangelisation’ inside the Church, to a given Pope).

This fact about the invented lexicon makes terminological work essential. Terms need to be specified for meaning to ensure consistent use.

We Salesians are a ‘knowledge society’ inasmuch as we pass on our knowledge in educated ways, through written documents often. This does not ignore the fact that the charism also transmits in much more flexible, viva voce contexts, or through non-verbal symbols, but we cannot deny the written culture so strong in the Church, post-Gutenberg and in the Salesian Congregation post-Don Bosco!

Sector terms don’t shift meaning much, or at all. If they do we drop the term! Sector terms should be valid anywhere in any language and culture. Sector terms are denotative rather than connotative.

These are all reasons for doing our work on terminology.

And in this context, translators beware! Given the specific and univocal nature of sector language you are either right or wrong!

|

1.13 ANS and ‘journo’ translation |

▲back to top |

Cronica (chronicle, daily news) is also denotative, specific, a style all its own. TM (translation memory) apparently has less application here. But style? Well, that doesn’t change, remains consistent! Standard Italian news reporting is different to how other cultures and languages manage it. We find much more need to adapt sentence structure, even create paragraphs where they don’t exist. In fact there is an argument that the ANS translator should simply note the details then put the original away and rewrite the details in his own language, rather than ‘translate’ it.

|

1.14 Ideology |

▲back to top |

We all have ideologies; it is part of being a human being who is not only a culture creator but an ideology maker. And of course, a charism is an ideology too.

Now, I can only really be a faithful translator of the charism if my ideology and the charism share something in common! An Italian popular song might have put this nicely some years back:

un’idea, un concetto, un’idea

finché resta un’idea

è soltanto un’astrazione.

Se potessi mangiare un’idea

avrei fatto la mia rivoluzione.

|

1.15 Do I know a word? |

▲back to top |

A word, a simple lexical item is more complex than it looks. To know it I should know:

- its etymology

- its history

- its meaning

- its pronunciation

- its spelling

- its social register

- its collocation with other words

- its morphology

|

1.16 A cautionary tale |

▲back to top |

The ‘dragoman’ was a European who knew Arabic, Turkish, Persian and interpreted between the Christian and Moslem world—it was a dangerous task! That’s how we got traduttore-tradittore, it seems, when the dragoman got it wrong. He could be executed for treason, where the ‘t’ stands for ‘translate’!).

|

1.17 Seeing (or being) double |

▲back to top |

I don’t know who said this but it struck me at the time as being true, and still does: “Translation is this bizarre skill—for those who have not tried it—that requires you to be fully engaged in grasping the meaning of a source text while at the same time disengaging to report on what you see. You have to be two people at the same time: an understanding self and a writing self. “

|

1.18 Border problems |

▲back to top |

Five Englishmen in an Audi Quattro arrive at the Italian border.

The Italian Customs agent stops them and says, “It's illegal to put 5 people in a Quattro.”

“What do you mean it's illegal?” asked the Englishmen. “Quattro means four,” replies the Italian official.

“Quattro is just the name of the automobile,” the Englishmen retort disbelievingly. “Look at the papers: this car is designed to carry 5 persons.”

“You can't pull that one on me,” replies the Italian customs agent. “Quattro means four. You have five people in your car and you are therefore breaking the law.”

The Englishmen replies angrily, “You idiot! Call your supervisor over—I want to speak to someone with more intelligence!”

“Sorry,” responds the Italian official, “he can't come. He's busy with 2 guys in a Fiat Uno.”

|

1.19 Please mind the gap |

▲back to top |

What a gap there can be between languages! Some languages are much more wordy than others, so what do I do when confronted with: “I signori viaggiatori sono pregati di fare attenzione allo spazio vuoto tra il binario e la banchina”? Please mind the gap!

|

1.20 Culaccino |

▲back to top |

Italian: Culaccino. The mark left on a table by a cold glass. Who knew condensation could sound so poetic!

|

1.21 Madonna |

▲back to top |

G. K. Chesterton throws an interesting light on this term:

“I was brought up in a part of the Protestant world which can best be described by saying that it referred to the Blessed Virgin as the Madonna. Sometimes it referred to her as a Madonna; from a general memory of Italian pictures. It was not a bigoted or uneducated world; it did not regard all Madonnas as idols or all Italians as Dagoes. But it had selected this expression, by the English instinct for compromise, so as to avoid both reverence and irreverence. It was, when we came to think about it, a very curious expression. It amounted to saying that a Protestant must not call Mary ‘Our Lady,’ but he may call her ‘My Lady.’ This would seem, in the abstract, to indicate an even more intimate and mystical familiarity than the Catholic devotion. But I need not say that it was not so. It was not untouched by that queer Victorian evasion; of translating dangerous or improper words into foreign languages. But it was also not untouched by a certain sincere though vague respect for the part that Madonnas had played, in the actual cultural and artistic history of our civilization. Certainly the ordinary reasonably reverent Englishman would never have intended to be disrespectful to that tradition in that aspect; even when he was much less liberal, travelled and well-read than were my own parents. Certainly, on the other hand, he was entirely unaware that he was saying ‘My Lady’; and if you had pointed out to him that, in fact, he was generally saying ‘a My Lady,’ or ‘the My Lady,’ he would have agreed that it was rather odd.”

|

1.22 Three languages |

▲back to top |

A folktale by the Brothers Grimm might be of interest.

An

aged count once lived in Switzerland, who had an only son, but he was

stupid, and could learn nothing. Then said the father: ’Hark you,

my son, try as I will I can get nothing into your head. You must go

from hence, I will give you into the care of a celebrated master, who

shall see what he can do with you.’ The youth was sent into a

strange town, and remained a whole year with the master. At the end

of this time, he came home again, and his father asked: ’Now, my

son, what have you learnt?’ ’Father, I have learnt what the dogs

say when they bark.’ ’Lord have mercy on us!’ cried the father;

’is that all you have learnt? I will send you into another town, to

another master.’ The youth was taken thither, and stayed a year

with this master likewise. When he came back the father again asked:

’My son, what have you learnt?’ He answered: ’Father, I have

learnt what the birds say.’ Then the father fell into a rage and

said: ’Oh, you lost man, you have spent the precious time and

learnt nothing; are you not ashamed to appear before my eyes? I will

send you to a third master, but if you learn nothing this time also,

I will no longer be your father.’ The youth remained a whole year

with the third master also, and when he came home again, and his

father inquired: ’My son, what have you learnt?’ he answered:

’Dear father, I have this year learnt what the frogs croak.’ Then

the father fell into the most furious anger, sprang up, called his

people thither, and said: ’This man is no longer my son, I drive

him forth, and command you to take him out into the forest, and kill

him.’ They took him forth, but when they should have killed him,

they could not do it for pity, and let him go, and they cut the eyes

and tongue out of a deer that they might carry them to the old man as

a token.

The

youth wandered on, and after some time came to a fortress where he

begged for a night’s lodging. ’Yes,’ said the lord of the

castle, ’if you will pass the night down there in the old tower, go

thither; but I warn you, it is at the peril of your life, for it is

full of wild dogs, which bark and howl without stopping, and at

certain hours a man has to be given to them, whom they at once

devour.’ The whole district was in sorrow and dismay because of

them, and yet no one could do anything to stop this. The youth,

however, was without fear, and said: ’Just let me go down to the

barking dogs, and give me something that I can throw to them; they

will do nothing to harm me.’ As he himself would have it so, they

gave him some food for the wild animals, and led him down to the

tower. When he went inside, the dogs did not bark at him, but wagged

their tails quite amicably around him, ate what he set before them,

and did not hurt one hair of his head. Next morning, to the

astonishment of everyone, he came out again safe and unharmed, and

said to the lord of the castle: ’The dogs have revealed to me, in

their own language, why they dwell there, and bring evil on the land.

They are bewitched, and are obliged to watch over a great treasure

which is below in the tower, and they can have no rest until it is

taken away, and I have likewise learnt, from their discourse, how

that is to be done.’ Then all who heard this rejoiced, and the lord

of the castle said he would adopt him as a son if he accomplished it

successfully. He went down again, and as he knew what he had to do,

he did it thoroughly, and brought a chest full of gold out with him.

The howling of the wild dogs was henceforth heard no more; they had

disappeared, and the country was freed from the trouble.

After

some time he took it in his head that he would travel to Rome. On the

way he passed by a marsh, in which a number of frogs were sitting

croaking. He listened to them, and when he became aware of what they

were saying, he grew very thoughtful and sad. At last he arrived in

Rome, where the Pope had just died, and there was great doubt among

the cardinals as to whom they should appoint as his successor. They

at length agreed that the person should be chosen as pope who should

be distinguished by some divine and miraculous token. And just as

that was decided on, the young count entered into the church, and

suddenly two snow-white doves flew on his shoulders and remained

sitting there. The ecclesiastics recognized therein the token from

above, and asked him on the spot if he would be pope. He was

undecided, and knew not if he were worthy of this, but the doves

counselled him to do it, and at length he said yes. Then was he

anointed and consecrated, and thus was fulfilled what he had heard

from the frogs on his way, which had so affected him, that he was to

be his Holiness the Pope. Then he had to sing a mass, and did not

know one word of it, but the two doves sat continually on his

shoulders, and said it all in his ear.

|

1.23 ‘i’ before ‘e’ |

▲back to top |

‘i’ before ‘e’ except when you run a feisty heist on a weird beige foreign neighbour!

|

1.24 Grammar police |

▲back to top |

|

1.25 One language helps another |

▲back to top |

There is a less known side of ‘translation’ in the Salesian context, and here I speak as a member of a Region that uses English as a ‘lingua franca’ a means of communication, in a geographical area that has maybe up to half of the world’s languages in it! We don’t use all 3,000 of those, but we do use at least 17 of them!

Those who have English as a first language can help those who have it as a second, third, or even fourth language. Here is an example, typical of news items I receive, “to be made beautiful’, as my confrere requests. There is no problem here at all—he feels at complete ease in writing in ‘his’ English, and I have no difficulty at all understanding what it is he wants to say in mine. Thus we can make sentences like the following ‘beautiful’:

“As well drowned much attention on the planned of a scholarship fund for the poor students will be launched next year.”

And:

“He highlighted the practice of the band role between mission territory with the potential resources found from the people who admire DB's spirit. Especially he didn't hide his desire to excavate the new benefactors to support missionary work starting from the base of the visibility and credibility that we Salesians have in society.”

When you know the individual well and ‘heart speaks to heart’, this is an added service of translation.

|

1.26 Faithful but not literal |

▲back to top |

The following discussion from Umberto Eco in his book ‘Experiences in Translation’, is very revealing, coming as it does from a master in the art:

“In my novel Foucalt’s Pendulum there is, at a certain moment, the following dialogue (I have simplified matters by putting the names of the speakers at the beginning, as in a theatrical text):

Diotallevi — Dio ha creato il mondo parlando, mica ha mandato un telegramma

Belbo — Fiat lux. Stop. Segue lettera.

Casaubon — Ai Tessalonicesi, immagino.

This is a piece of sophomore humour, a handy way of representing the characters’ mental style. The French and German translators, for instance, had no problems:

Diotallevi — Dieu a créé le monde en parlant, que l’on sache il n’a pas envoyé un télegramme.

Belbo — Fiat lux, stop. Lettre suit.

Casaubon — au Thessaloniciens, j’imagine. (Schifano)

Dioteallevi — Gott schuft die Welt, indem er sprach. Er hat kein Telegramm geschikt.

Belbo — Fiat lux. Stop. Brief folgt.

Casaubon — Vermutlich an di Thessalonicher. (Kroeber)

A literal translation in English would be:

Diotallevi — God created the world by speaking. He didn’t send a telegram.

Belbo — Fiat lux. Stop. Letter follows.

Casaubon — To the Thessalonians, I imagine.

William Weaver, the English translator of Foucault’s Pendulum, realised that this exchange focuses on the word lettera, which is used in Italian both for mailed missives and the messages of St Paul (the same applies in French) — while in English the former are letters and the latter epistles. This is why, together with the translator I decided to alter the dialogue and to reassign the responsibility for that witticism:

Diotallevi — God created the world by speaking. He didn’t send a telegram.

Belbo — Fiat lux. Stop.

Casaubon — Epistle follows.

Here Casaubon takes on the double task of making the letter-telegram pun and the reference to St Paul at the same time. In Italian the play was on two homonyms (the reference to Paul had to be inferred from the double sense of the explicit word lettera); in English it is on synonyms (the reference to the current formula on telegrams had to be inferred from a quasi-explicit reference to Paul and from the weak synonymy between epistle and letter).

Can we say that this is a faithful translation of my text? Note that the English version of the exchange is snappier than the Italian, and perhaps some day, on making a revised edition of my novel, I might use the English formula for the Italian original too. Would we then say that I have changed my text? We certainly would. Thus the English version is not a translation of the Italian. In spite of this the English text says exactly what I wanted to say, that is, that my three characters were joking on serious matters —and a literal translation would have made the joke less perspicuous.

The above translation can be defined as ‘faithful’, but it is certainly not literal.”

|

1.27 I’m not a dictionary, but a thesaurus? Yes! |

▲back to top |

Translators complain that people sometimes think they are walking dictionaries. Apart from the false notion of one-to-one equivalence that lies behind the dictionary idea, it does not matter how well you know a language—you still do need a dictionary to supplement your knowledge. On the other hand, over-reliance on dictionaries often leads to the choice of false synonyms and the ‘sin’ of dictionary fundamentalism. A thesaurus might lead you to false synonyms, in spades, but it will certainly lead you away from dictionary fundamentalism.

We know (well, at least I know, since I’ve translated much of his stuff and have done a corpus analysis of it) that Don Bosco had a daily-use vocabulary in Italian of around 8 to 9,000 words, which wasn’t bad considering his L1 was Piedmontese. Of course there are terms that are ‘dated’ and not in use now, or not much, like tosto, poscia … and his spelling was, mutatis mutandis, (Phew! Glad I got the spelling of that last word correct!) a bit like Shakespeare’s, but once you get the hang of that, he is not so difficult to work with.

The Salesian ‘lingo’ has expanded, but it is still a ‘sector’ language, with a good number of precise, denotative meanings.

And then there is Italian per se. And this is where you need a (and need to be a) thesaurus! Some well-loved phrases pop up in every other Italian document and have no clean, catch-all English translation. More to the point, you need to avoid the trap of always translating them the same way, the good old stock phrase standby! It annoys your readers no end!

On any 14 occasions you might translate a fronte di as: compared to, while, although, notwithstanding, in light of, in the face of, faced with, confronting, related to, for, against, over, with, in exchange for.

Or consider that fun word the FMA chose instead of dicastero ,—ambito. You see, it turns up in almost any context you can name. Here are 26 possibilities (and still counting) for a range of grammatical contexts for ambito: sphere, realm, context, within, domain, area, scope, in terms of, with a view to, will also include, for that purpose/on that occasion, as part of, as far as the … is concerned/with regard to, through/by, in the case of, in the....place, within the scope/according to, in their sphere of activity (this is one I often use for the FMA ambito), purview, within the framework of, for the purposes of, extent, range, compass, field, as part of, in the context of, in, environment, circle, ambit, confines, region, area, orbit, province.

Or try essenziale, which turns up a number of times in the ambito of the da mihi animas cetera tolle, more particularly the cetera tolle: sleek, simple, basic, essential, unadorned, straight-forward, plain, austere, spare, clean, minimalist, humble, natural, no-frills, modest, lean, streamlined, indispensable, practical, must-have [in some contexts, e.g. fashion].

Or try the old favourite intervento. Why be stuck with ‘intervention’, when in context it could easily be: [left out], measures, steps, actions, aid, assistance, attendance, presence, comment, remark, cut-off, help, intercession, agency, interjection, interference, operation, paper, presentation, participation, project, involvement, report, request to speak, speech, address, talk, to operate, work, contribution, contributed paper ...

|

1.28 King context |

▲back to top |

What a demanding monarch! When in Rome …. ! Every translator knows how important context is, of course, but Italian culture and habits become so ingrained (for the Italian to English translator, naturally, and I’m not talking about which cheek and how many times to kiss it) that it can be hard to escape them. You may find yourself saying ‘Good Sunday’ where you’d be better not saying anything because we just don’t say it in English. (I would reply ‘Good Lord!’; it would at least be fitting).

But there are more subtle habits still, especially in writing. Let me list a few: big words, long sentences (indeed, paragraphs), linking words (infatti, inoltre …), more is better (Why say ‘no smoking’ when you can say in questo locale è severamente vietato fumare), free-flowing-intertextual reference (try reading Umberto Eco).

|

1.29 When the shoe is on the other foot |

▲back to top |

Don’t you just love it when Italy decides to do its own English translation? Menus and tourist brochures are amongst the classic examples. Let’s visit one of Tuscany’s seaside wonders …

Antignano

“Suggestive beaches with gravelly fund, not always easily accessible, in a line of coast characterized by dark rocks. The first one is the “Beach of the Tamerice”, so-called for the presence of a historical tamerice, withdrawn by important painters as Factors, Christmases and Lomi…. Suffered to south there is the ” Beach Longa “, that as it says the name it is one of the longest of Antignano, also it in front of the street that brings the same name, that is Street Longa. Impossible besides to confuse her. Little bottom there is one of the most suggestive beaches of this territory: the “the Ballerina’s Beach”, to which is entered by the homonym park, through a carpet of in bloom margherite under the tamericis. The scaletta a spiaggetta of gravel going down is reached, surrounded by rocky faraglioni. Just one of these, before an excessive erosion, it vaguely seems a ballerina remembered, from which the name.”

As for menus, ever tried “mushrooms with ham pants” (calzone con funghi e prosciutto), “first flats” (primi piatti—first courses), or “cooked queers” (finocchi al forno—baked fennel)?

So where does this sort of thing come from (other than from Google Translate)? One exasperated IT>EN translator put it this way:

“But perhaps the most primal reason for the Italian approach to English—a bias that Italians carry with them (as they like to say) “in their DNA”—lies in their endemic certainty that Italian is a complex, eloquent language while English is a simple, rather vapid one. English, in other words, is a language that Italians are forced to contend with, but that doesn’t make it a language worthy of respect.

One example will suffice: In January 2010, La Repubblica published a piece on lexical impoverishment among the young, focusing on the spread of teen slang and “text talk” (Balbi, 2010). Comments poured in from La Repubblica’s readers, many of them certain that blame for the presumed deterioration of the Italian language could be laid squarely at the feet of English. The invective reached its apogee when one reader wrote:

‘The Italian language is extraordinary and difficult precisely because of its enormous expressive richness—unlike American English, which represents the sanctification of ignorance carried to the extreme. The emulation of inane levels of linguistic lunacy and their diffusion among the younger generation is only the latest aberration imported from America. As if deregulation, globalization, revolving credit, rap music, sagging, television with more commercials than programming, reality shows, and McDonald’s weren’t enough.’” (Wendell Ricketts).

|

1.30 TEnT |

▲back to top |

Actually, TEnT is a term that is sometimes used to cover a range of computer-assisted approaches to translation, and it’s not such a bad term, really, standing for Translation Environment Tool.

These days, one would be silly not to work within a TEnT. The thing is to find the best way to do so. Here are a few random thoughts on the matter.

We are talking about setting up a suitable translation environment that makes use of digital tools—an editing and translating environment, no less.

The environment will contain at least the following:

- an input method. Some swear by voice recognition. I haven’t found that useful. I swear by (and occasionally at) the keyboard. I like an international keyboard rather than a US one. For someone translating more often than not from Italian, Spanish or French, an Italian or Spanish keyboard is excellent for my purposes because it is QWERTY, but not a French one! (which is AZERTY and throws me off every time)! And if I can only find a US QWERTY, I simply go online and buy a set of Italian keyboard stickers and stick them on the appropriate keys, leaving the original visible as well so you have the best of both worlds. Then it only remains to ask your operating system (with Linux it is simple) to give you the choice of keyboards, such as IT, ES, EN and maybe PT and PL as well for all the other accents you might need on the odd occasion.

- Spellcheck. Always need that, more for typos than for inability to spell, though constant switching across languages often seems to confuse that part of the brain which deals with spelling.

- File preparation. Depending on how you receive your files, what kind of text it is (is it a Presentation format for example?), what file extension it has, you may need to do some preparation work. If it is .pdf the first prep activity is to approach whoever gave it to you and ask them to give you their original, since .pdf always has a non-pdf original, usually .doc or something like that. If they haven’t got it, then you have to do the best you can. Some PDF readers will allow you to export to text only. Things may be more difficult still if someone has scanned the text. OCR is not an exact science. It is better to reduce everything to text only and fix the errors before doing anything else.

- Segmentation.This is where computer translation programs come into play, since they segment text (usually in sentences, but you can alter that), meaning you don’t get distracted. You simply translate the sentence in front of you. All formatting, footnotes etc are taken care of in such a way you don’t have to worry about them.

- Editing. It is text and you will need to edit at some stage.

- Quality. It helps if the environment you are working in highlights errors for you or alerts you to quality issues.

- Generate results. You may have made a number of alterations to the original as part of the translation process. You now want it all back together again as the ‘translated original’. How wonderful if that could be automated.

For all these things in a single environment I use a truly free, cross-platform program called OmegaT.

|

1.31 Another translation habitat |

▲back to top |

While talking about tents and translation environments, we are encouraged these days, in our more ecologically sensitive world, to be aware of our habitat, and as one writer has put it, ‘A delicate world of punctuation lives just beneath the surface of your work, like a world of micro-organisms living in a pond. They are missed by the naked eye.’ (Noah Luke, A Dash of Style: The Art and Mastery of Punctuation W.W. Norton and Co. 2007). We could extend that idea beyond punctuation, for in many ways the sounds and symbols of a language are bit like micro-organisms too – they function together within the habitat of a particular language in such a way that they do not strike the consciousness of the native speaker, and should not. But they will look or sound ‘foreign’ to anyone else.

|

1.32 Translation—a divine act |

▲back to top |

This first appeared in the EAO blog on sdb.org on 30-09-2010 and received a comment from a Belgian translator, also reproduced below:

There are any number of hard-working translators around our Region; Salesians, Sisters, lay people. It is one of the more thankless tasks, occupying many hours. It is a task that requires competence and perseverance. I am trying to urge the Congregation to think of it not as a 'problem', racing to find an immediate answer to a demanding question like 'now who can we find to get this into Spanish, or English or Chinese - tomorrow?) (Usually with the emphasis on 'tomorrow')? Translation doesn't work like that, unless it's of the simultaneous interpretation kind, which is not, technically, known as 'translation', but indeed, simultaneous interpretation.

But did you know that at least two significant Christian writers have taken the view that translation is a divine act which marks out Christian history in a particular way? One of them is particularly significant because, while a Catholic now, he grew up a Muslim and encountered Jesus for the first time in the Koran, a book which of its very nature is never translated.

The view taken by both Lammin Sanneh (Gambian born Muslim, now professor of missions, world Christianity and history at Yale Divinity School, and Andrew Walls OBE (Scotland) is that the Incarnation was an act of translation, Christianity is a translated religion and has been a force for translation throughout history - most languages have grammars and dictionaries because of the work of Christian missionaries. And anybody who knows anything about Salesian missions and missionaries around the world over 135 years knows that despite being Johnny-come-latelies in the history of Christian missions, this contribution to languages and cultures has been notable. Think north-east Indian hill tribes, the Shuar of Peru and Ecuador, the Xavantes in Brazil, just for starters.

Thus translators of EAO and elsewhere, be proud! Yours is a metaphor for mission, and maybe the Congregation could tackle the issue from this perspective rather than from the day-to-day emergency one.

Comment:

I am

very, very pleased with this text. After more than 40 years of

missionary work in the RDC (the former Belgian Congo) I had to stay

in Belgium because of kidney trouble. So I started working on the

computer at the age of 74. I have now been translating for the

province (BEN) for nearly ten years. I have never considered it as a

divine act but as a most humble missionary work.

Thank you for

such a magnificent appreciation.

Father Gaston De Neve SDB

|

1.33 Getting it wrong |

▲back to top |

The more literary and therefore connotative a text is, the more leeway there is for translating it in different ways, and several versions could therefore be considered to be ‘correct’ in overall terms. But you can still ‘get it wrong’! Religious texts, especially Scriptures, are less forgiving, given the importance of God’s Word. But it is interesting that the ‘daddy’ of all Scripture translation, St Jerome, could also ‘get it wrong’. He translated the Hebrew word ‘almah’ as virgin: “Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Emmanuel” (Isaiah 7:14). Translators today realise that the word only means a young woman who can become a mother. It is obvious from this that the connotation of the verse changes completely if the word is translated as virgin. Mistranslated as it may be, St Jerome’s translation has, over the centuries, attained a sort of finality.

|

1.34 Alice in Wonderland, Humpty Dumpty and all that |

▲back to top |

“When

I use a word,” said Humpty Durnpty, “it means just what I choose

it to mean—neither more or less.”

“The

question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so

many different things.”

“The

question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master —

that’s all.”

— Lewis

Carroll, from Alice in Wonderland

“The translator who understands his job feels, constantly, like Alice in Wonderland trying to play croquet with flamingoes for mallets and hedgehogs for balls; words are forever eluding his grasp.” (Ronald Knox from his Englishing the Bible.)

You only have to think of Humpty Dumpty in languages other than English to realise how translators have to be faithful to their target language as much as the source language. Humpty goes on, in his discussion with Alice, to tell us that “They’ve a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they’re the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs ...”:

In English, the verb is marked for tense: Humpty ‘sat’.

In Indonesian, the verb would not alter for tense.

In Russian, the verb would also tell us if our anthropomorphic egg was male or female and whether Humpty was sitting for a long time or had had a great fall (complete or incomplete action).

In Turkish, the verb would tell us how we came by this information: did we see Humpty ourselves or did we hear about him from someone else?

In Pitjantjatjara, an Australian aboriginal language, the verb ‘to sit’ is equivalent to the verb ‘to be’, so Humpty takes on a far more philosophical position than at first we realise!

In Fijian, the conversation between Alice and Humpty would have started by Alice asking, “Where are you going?”, followed by ‘How old are you?” and maybe even “Are you married?” Humpty would not need to give any definite answers to any of these, just a flick of the head (but not enough so that he falls off the wall!)

So who is the master then? The reader, the words, the source language, the target language … ?

|

1.35 Being bicultural |

▲back to top |

A translator needs to be a bit more than bilingual; in many cases one needs to be bicultural as well. This goes beyond the question of idiom translation, things like ‘pigs fly’ (Italian pigs don’t but their asses do!) There is a Salesian culture after all and it goes beyond idioms or lexical differences; it is a way of thinking. We notice it every time a translation is outsourced. Rare is the occasion when a non-Salesian (as in non-member of the Salesian Family or at least ‘friend of Don Bosco’) can produce a perfectly acceptable translation of a Salesian text.

|

1.36 Translation genre – web |

▲back to top |

Translating for the web (I am thinking of a website such as sdb.org which is intended to present in at least five languages, or ANS which aims at six, but also local websites in languages other than English) is an exercise affected by the medium itself. This aspect of translation needs further understanding.

Let’s assume that some of the texts involved in this case are ‘web texts’, i.e. texts written especially or mainly for the fact that they will appear on the web. These texts have certain characteristics:

- Generally shorter, because people read less content on a web page;

- Choice of wording is important because web users rely on keywords for finding the info they seek through search engines, but also because web users typically scan titles, subtitles and highlighted parts for information. As a consequence we must avoid bland words, made-up words, and information deferred to the end of the text (as it may well be missed).

- Text has to be generally more easily understandable.

The translator on the web is often a ‘localiser’ (adapting text to web users in a culture and language) and therefore a cultural mediator.

Web translation more often than not requires some appreciation of the ‘languages’ (html and associated languages) which underlie the presentation on screen. You may no longer be working with Word (or similar) documents but with tagged text and/or code.

In fact this introduces a new challenge for the translator, since he must be able to distinguish between code/tags and ‘translateables’ or strings of text to translate. This is best done by using programs which do this separation for you and ensure that you are only dealing with the translateables and not mistakenly translating code.

Web texts are easily modified/updated. This means a translator may often be working not with the whole text but with modifications/updates or decontextualised segments. This generally means more literal translation.

|

1.37 Translator as inter-cultural mediator |

▲back to top |

Because of the focus on missionary activity in the Congregation, there have been certain regions (e.g. America South Cone, South Asia) where translation needs and responses have been prominent in the past. These days we look upon every region, every Salesian as ‘missionary’, so we need thoughtful, reflective translators who are aware that it is a Gospel and a charism they are translating, and that they are at the very least operating as inter-cultural mediators.

|

1.38 Translation and interpretation |

▲back to top |

There is quite a difference between translation and interpretation. At any kind of international gathering there is probably a combination of both activities. One may receive a text beforehand to translate, but then that text is ‘delivered’ viva voce. Rarely does a speaker simply read it. If he does, of course, no further activity by the ‘translator’ is involved. But if the text is not read, or is added to, subtracted from, or used as a basis, or simply ignored (a not infrequent situation), then interpretation comes into play.

There are three possible settings for interpretation, and the techniques need to change for each of them: one may be in a soundproof booth, or in a crowd, where the speaker pauses for subsequent translation, or in a ‘whisper’ circumstances, beside one or more who need translation. But you are always interpreting in these cases—expressing ideas orally that you have heard viva voce.

And the skills? You listen to what the speaker says, translate that in your mind, put it into words in your target language and (unless there are pauses) do this while the speaker is continuing to speak. It requires a mental miracle and that is why it is such a complex and demanding task.

There is a mnemonic to follow for someone who is not accustomed to this task:

In advance: familiarise yourself with the topic.

Note down main points.

Translate and clarify the meaning of main terms beforehand if possible.

Establish a relationship with the speaker, even if the minimum is to be able to watch his lips.

Remember to pronounce words clearly and distinctly.

Produce a brief summary of the talk, especially if there are questions to follow.

React quickly and be able to work under pressure.

Enjoy the task.

Transmit a clear message.

And within what we could call ‘ethical limits’, be ready to bluff! You will not catch every word, maybe not even every idea and you have no time even to complain about that (afterwards maybe!)

And if it’s a joke you are translating, and you don’t understand it (= can’t make it sound funny in the target language), then say something like: “He’s telling a joke” to which you may, if you are game, add “So laugh!”

|

1.39 Allowing the Web to help us |

▲back to top |

There are some extraordinary aids available to the translator on the world wide web, depending, to some extent on the language pairs we need to work with. I can only speak of experience with language pairs that I have had to work with, for the most part English as the target language and Italian, Spanish, French or Portuguese as the source language (occasionally German).

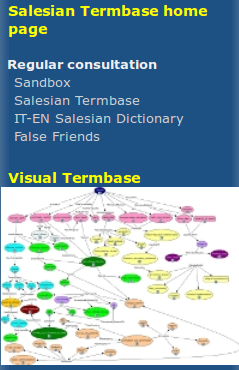

If it is Salesian material we are dealing with, and it tends to be specialised, then I would make use of Salesian Termbase, available from http://www.sdb.org or http://bosconet.aust.com. This will be especially helpful for the ‘it-en’ pair, but may help any Salesian translator who knows both Italian and English, although needing to translate into a different target language.

The termbase, once its homepage is accessed from the illustrated button on sdb.org or directly at Bosconet homepage, offers a terminological resource accessed by clicking on ‘Welcome to Salesian termbase’. This permits one either to enter a term (in English or Italian) or use the alphabetical listing. Descriptions are in English, but the original term (usually though not always Italian) will appear as well.

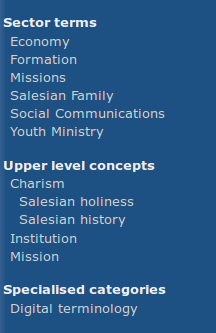

This is not the only resource available from that page. There is also a bilingual (it-en) glossary or dictionary, a help list of false friends, and a visual representation of Salesian terminology:

There is another way too, to use the termbase, since all terms are allocated a Salesian subdomain. It can be helpful to see associated terms in a subdomain:

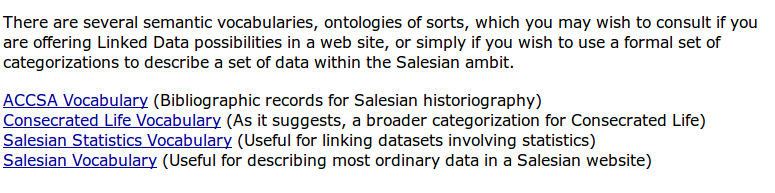

There is one more resource available from Salesian termbase, though this is a much more specialised and technical one. Termbase provides access to a number of ontologies (structured terminologies) for use in linked data on the web:

M ore

general excellent web resources for translators in a variety of

language pairs would include (other than web translation resources

like Google Translate):

ore

general excellent web resources for translators in a variety of

language pairs would include (other than web translation resources

like Google Translate):

Linguee at http://www.linguee.com/: this is an excellent resource, constantly under construction, which provides real contexts for terms, based on corpus collections. Ideally we could do similarly with a Salesian corpus in the future:

Another term resource is known as IntelliWebSearch: http://www.intelliwebsearch.com

This item needs to be downloaded (free) and installed. It then highlights terms for you as you do web searches.

|

1.40 Proper Nouns: pegs on which to hang a set of properties! |

▲back to top |

Italian style suggests that we do not simply repeat the subject word for word each time, but vary our way of doing so. In an ANS news item, Italian original, ‘Don Bosco’ will be mentioned first up, but subsequently becomes ‘the Saint of the young’, ‘the priest from Valdocco’, and so on—all in the space of a paragraph. Salesians can be Salesians to begin with, but soon become ‘Don Bosco’s sons’, ‘the religious’. The Prime Minister of Italy, currently Enrico Letta as this is being written, may be referred to as the Presidente del Consiglio. It would be a mistake to translate this as ‘President of the Council’. The Italian journalist simply means he is Prime Minister. English will be happy if Milan is referenced several times in a paragraph or article, but not Italian. It will be subsequently referred to as ‘the capital of Lombardy, ‘Italy’s fashion capital, ‘the business capital’. Umberto Eco’s comment about ‘every Proper Noun is a peg on which to hang a set of properties’ comes true here! Reading some news items in Italian, including ANS ones, is like facing up to a trivia quiz (well, this is what it looks like to me; I am sure an Italian journalist would not agree!) The point is that if we translate as we find it, the English begins to sound over-inflated and decidedly odd.

|

1.41 False friends |

▲back to top |

Since Italian is more Latinate than English, and bearing in mind the question of ‘register’ (Latin = educated, French = upper-class and exotic, German = down-to-earth), the translator has to be very much on guard: ‘veracity’ v. ‘truth’, ‘lateral’ v. ‘side’, ‘verdant’ v. ‘green’ etc. It goes well beyond register however. There are so many ‘false friends’, using this as a generic term here to cover false cognates and some phrases as well, that can waylay us when translating from Italian to English. The following lists are all traps along the pattern of the first in the list: infatti translated as ‘in fact’ where it may mean ‘indeed’ and more often than not could be completely ignored.

infatti = ‘in fact’ when it really means ‘indeed’

attualmente used to mean ‘actually, …’ when it means ‘currently’

simpatico = ‘sympathetic’ where it really mean ‘pleasant, friendly’

secondo me = ‘according to me’, but would be better as ‘in my opinion’

conoscere = ‘to know’ when in the context of ‘to meet (for the first time)’

libreria = ‘library’, but is really a bookshop

lettura = ‘lecture’ when it means ‘reading’

conferenza = ‘conference’ when it is really used to mean ‘lecture’

morbido = ‘morbid’ when it means ‘soft’

sensible = ‘sensible’ when it really means ‘sensitive’

eventuale, eventualmente = ‘eventual’ when it means ‘possible’ or ‘likely’

comprensivo = ‘comprehensive’ when it means ‘understanding’

assistere = ‘assist’ when it means ‘attend’ or even ‘be witness to’

controllo = ‘control’ when it means ‘check’

|

1.42 Loan words have a habit of changing meaning |

▲back to top |

English loan-words may be re-exported with changed meanings, as in the use of gadget to mean `freebie', `promotional item'. We need to be alert to this, since Italian happily accepts words from other languages, but may choose a gerund form and treat it as a noun, or may change its meaning entirely. Here are just a few of this kind:

autogrill = service station (where you can get something to eat)

autostop = hitch-hiking

camping = campsite

eskimo = parka

flipper = pin-ball machine

footing = jogging

notes = notebook

parking = car-park, parking garage

slip = underpants / knickers (so, applicable to both male and female)

stage = training course

toast = toasted sandwich

tilt = no longer working properly! Just as pin-ball machines go dead and display TILT when shaken, the espression andare in tilt has become an Italian cliché.

|

1.43 Emerging metaphors |

▲back to top |

Consider: itinerario, percorso, cammino, tappa, accompagnamento... This is an emerging Salesian metaphor set because even a minimal corpus study (easily done by reducing texts to simple text format then searching them for a term) shows us that these terms are found in the Memorie Biografiche almost without exception as physical or spatial references to a journey. But do the same thing with a contemporary Salesian corpus (I took a random 1,000 files from sdb.org to test this) and the result is as follows: itinerario di vita, di educazione alla fede, itinerario pedagogico, formativo, di formazione ai giovani, di crescita, di discernimento, di santificazione, di evangelizzazione, vocazionale, di preghiera, di liturgia, di vita sacramentale. The collocates for percorso are very similar, as are those for cammino: il cammino dei giovani oggi, spirituale e pastorale, di crescita e maturazione, di santificazione, di ascesi, di fidanzamento. And in the random modern corpus there were practically no uses of the terms in their literal physical journey sense, though there is no reason why there should not be; it would be perfectly legitimate.

|

1.44 Learning from the gentes |

▲back to top |

There is much talk these days about mission ad gentes. If the translator is someone with a mission, could we think about translation ad gentes by which I mean something in between translation ad verbum (literal) and translation ad sensum (freer), and which takes account of what the gentes are saying? This would help both those who produce our original texts and those who translate them. We have every right to our own Salesian language, we but have a duty too to see that it does not become overly special and precious. And how do we know what the gentes are saying? If we want to get a snapshot of what the Salesian gentes are saying at any one moment, we need a slice of representative Salesian language from across the world and some simple lexical analysis of it. For example, every six years in preparation for a General Chapter, Provincial Chapters send in their observations and comments to contribute to the Chapter theme and other issues that touch closely on Salesian consecrated life and activity—you could not get much more representative than that.

What

do the gentes

have to say about integrale

as ‘integral’? On the basis of the kind of activity suggested

above the evidence is they prefer terms like 'complete',

'all-rounded', 'holistic'. What happens if you have to translate the

term umanesimo integrale,

because, given that 'integral' in English primarily means 'essential'

(in the sense that something is only complete if it has it), my

feeling is that 'integral humanism' might lead people to think in

that direction, and what does 'essential humanism' mean? I don't

know! Tell me!

|

1.45 View from the mountain top |

▲back to top |

The received and popular wisdom regarding translation is that it must be anything but a glorious and priestly task. It sounds boring and must obviously be a hard slog. Requests may arrive at any hour and, in the internet age, from any quarter, usually with firm deadlines. Translation takes time—there are few short cuts despite technological aids, and if it is a large work, say a book of 200 or more pages, then it is something like climbing a mountain; you put one foot after the other and eventually get there. The view at the top, however, is a glorious one!