the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith

No sooner had the first Salesians established themselves

in Buenos Aires and San Nicolás than Don Bosco began

making his case for “missions” with the Roman authorities.

The essay on Patagonia mentioned above (1876) is a case

in point. Between 1876 and 1883 numerous exchanges and

negotiations took place to that effect.

In the 1876 memorandum to Card. Franchi (quoted

above), after laying out his strategy for the evangelization

of the native tribes out of San Nicolás, Don Bosco adds: “I

humbly ask your Eminence: [...] 3º to create a Prefecture

Apostolic that might exercise ecclesiastical authority over

the natives of the Pampas and of Patagonia, who up to now

have not been subject to any diocesan Ordinary nor to any

civilized government.”13 In a subsequent memorandum to

the same Prefect (1877), Don Bosco suggested the erection

of a Prefecture Apostolic at Carhué and of a Vicariate at Santa

Cruz.14 A little later (1878) in a letter to Cardinal Giovanni

Simeoni, newly appointed Prefect of the Congregation

for the Propagation of the Faith, Don Bosco proposed the

creation of a Vicariate or of a Prefecture at Carmen de

Patagones at the mouth of the Rio Negro. Here “two well

known [native] chiefs are asking for our missionaries, giving

assurance of help and protection.”15

Cardinal Gaetano Alimonda (Archbishop of Turin)

and Msgr. Dominic Jacobini were delegated to study the

proposal. Of this phase of the negotiations Don Bosco wrote

to Pope Leo XIII in 1880 (when the Salesian, though already

established at Patagones, had hardly begun any missionary

activity): “In obedience to Your Holiness’ command, I have

had a long conference with His Eminence Card. Alimonda

and with the Most Reverend Msgr. Jacobini. [...] It was a

common point of agreement that a Vicariate Apostolic

should be erected for the colonies [missions] established

on the Rio Negro, and that a seminary to train evangelical

workers should be founded in Europe.” In the detailed

“Report on the Salesian Missions” (that is, on the Salesian

work in Argentina and Uruguay) attached to this letter, Don

Bosco pointed out that the Argentine government had just

created the Province of Patagonia. He suggested that the

Vicariate might well take the same name and cover the

same territory, including all the lands to the east of the

mountain range of the Andes “until another Vicariate is

erected at Santa Cruz.” 16

13 Don Bosco to Card. Franchi, May 10, 1876, in ASC 131.01, FDBM 23

A3-6 (autograph) Ceria-Epistolario III, p. 58-61.

14 Don Bosco to Card. Franchi, December 31, 1877, Ceria, Epistolario

III, p. 256-261, transcribed in EBM XIII, 590-596. Carhué (in the Pampa

southwest of Buenos Aires) and Santa Cruz (on the Atlantic coast in

southern Patagonia) were military outposts. Fr. Cagliero declined these

offers.

15 Don Bosco to Card. Simeoni, [March] 1878, Ceria, Epistolario III, p.

320-321. In this letter Don Bosco also declares his willingness to prepare

missionaries “for the Vicariate of Mangalor, India, or some other mis-

sion.”

16 Ceria, Epistolario III, p. 567-575; EBM XIV pp. 500-508 (Don Bosco’s

Don Bosco’s “definitive” proposal was made, after

further consultations and negotiations, in a laboriously

worded memorandum to Cardinal Simeoni, on July 29, 1883.

This proposal was for three Vicariates and/or Prefectures.

Don Bosco suggested the immediate erection of a Vicariate

for Northern Patagonia (Rio Negro) with seat at Carmen

de Patagones, and a Prefecture for Southern Patagonia

(Santa Cruz). Central Patagonia (Chubut), still undeveloped

and “wholly under Protestant control,” would be under

the patronage of the northern Vicariate, until a separate

Vicariate could be established there. Similarly, the southern

Prefecture would remain under the general patronage of

the northern Vicariate, unless the Holy Father decided to

make it an independent Vicariate.

Requested to nominate candidates for these posts, Don

Bosco submitted the names of Fr. Cagliero or Fr. Costamagna

for the northern (and central) Vicariate, and Fr. Fagnano, for

southern Patagonia. Don Bosco commended the three as

“strong, hard-working men, good preachers, inured to toil,

and of unimpeachable moral character.” Fr. Fagnano, was

further commended as particularly suitable for southern

Patagonia, being ”a man of powerful physique and defiant

of toil and danger.”17

At this point (end of July 1883) Don Bosco rested his

case and waited for Rome’s decision. A few days before, the

Salesian work had been established in Niterói (Brazil).18

One month later, the Third General Chapter was

convened and held its preparatory spiritual retreat at San

Letter and Report to Leo XIII of April 13, 1880).

17 Don Bosco to Card. Simeoni, July 29, 1883, Ceria, Epistolario IV, p.

225-227; EBM XVI. pp. 295-296.

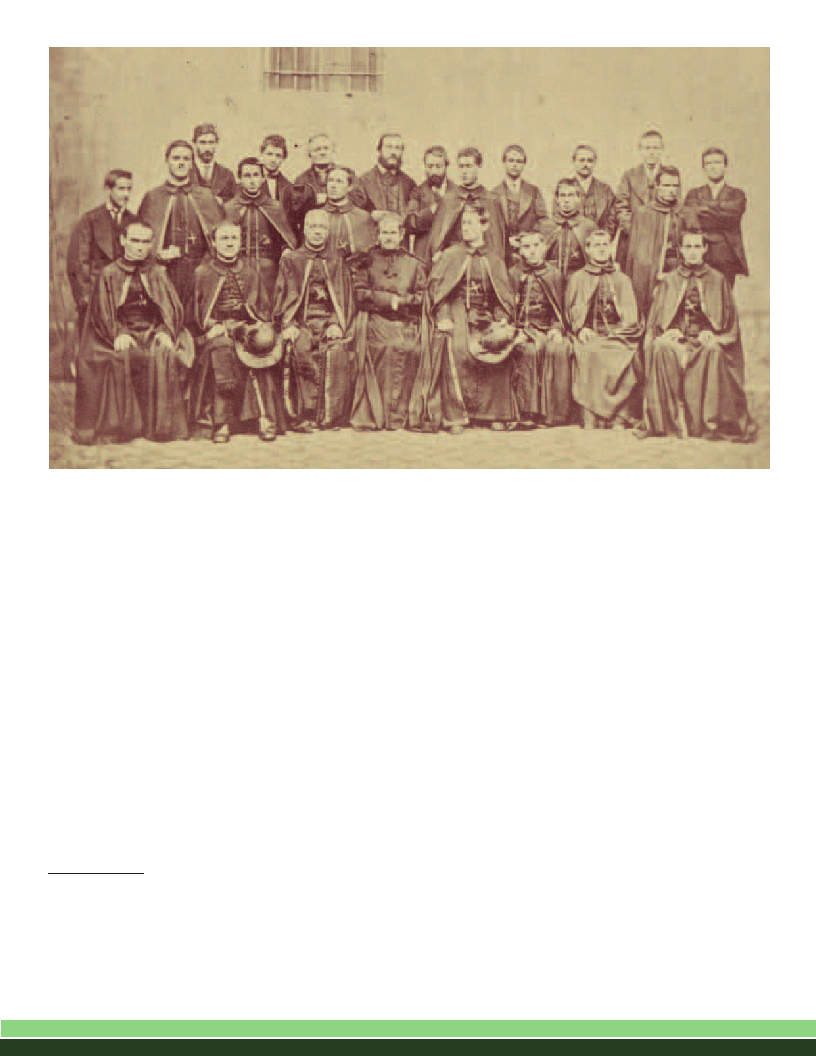

John Cagliero (1838-1926), one of the early followers of Don Bosco,

was ordained a priest in 1862, and led the first band of 10 Salesians to

South America, where as Don Bosco’s vicar from the start, he headed

the Salesian work and guided its development through the length and

breadth of the continent. He was appointed Vicar of Northern Patagonia

in October, and ordained bishop on December 7, 1884. Pope Benedict

XV made him a cardinal in 1915.

James Costamagna (1846-1921) was ordained a priest in 1868 and

served as local director of the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians

from 1875 to 1877. He led the third missionary party in 1877, and was

among the three missionaries who accompanied General Roca’s military

expedition in 1879 and made contact with the Araucan natives on the

Rio Negro. In 1880 he succeeded the deceased Fr. Bodrato as director

of the Pius IX school in Almagro (Buenos Aires), and as provincial he

founded the Salesian work in Chile in 1887. Nominated Vicar Apostolic

of Méndes y Gualaquiza (Ecuador), he was ordained bishop on May 23,

1895. While awaiting the opportunity to enter his Vicariate, he acted

as Fr. Rua’s representative for the Salesian works on the Pacific side.

He was permitted to visit Ecuador briefly in 1902, and then allowed to

enter his Vicariate permanently in 1912.

Joseph Fagnano (1844-1916) was ordained in 1868 and was a last-hour

substitute member of the first missionary group in 1875. He served as

first director of the school of San Nicolás, and in 1879 he was named

pastor of the parish of Patagones, whence his true missionary career

was launched. In November 1883 he was appointed Prefect Apostolic

of southern Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. Having established a base

at Punta Arenas in mid-1887, the indomitable Fr. Fagnano founded mis-

sions in Tierra del Fuego for the evangelization of the natives.

18 Cf. EBM XVI, pp. 288-291; Ceria, Annali I, p. 457-460.

5