12

GeTttHinEg tLoOKRnEoMw DIPoSnUBMosSco

January 2012 Study Guide

Institute of SalesiWanINSpTirEitRua2l0it1y6

ordinary revolution of human affairs. Happily, there

are schools in these prisons now. If any readers doubt

how ignorant the children are, let them visit those

schools and see them at their tasks, and hear how

much they knew when they were sent there. If they

would know the produce of this seed, let them see a

class of men and boys together, at their books (as I

have seen them in the House of Correction for this

county of Middlesex), and mark how painfully the full

grown felons toil at the very shape and form of letters;

their ignorance being so confirmed and solid. The

contrast of this labour in the men, with the less

blunted quickness of the boys; the latent shame and

sense of degradation struggling through their dull

attempts at infant lessons; and the universal eagerness

to learn, impress me, in this passing retrospect, more

painfully than I can tell.

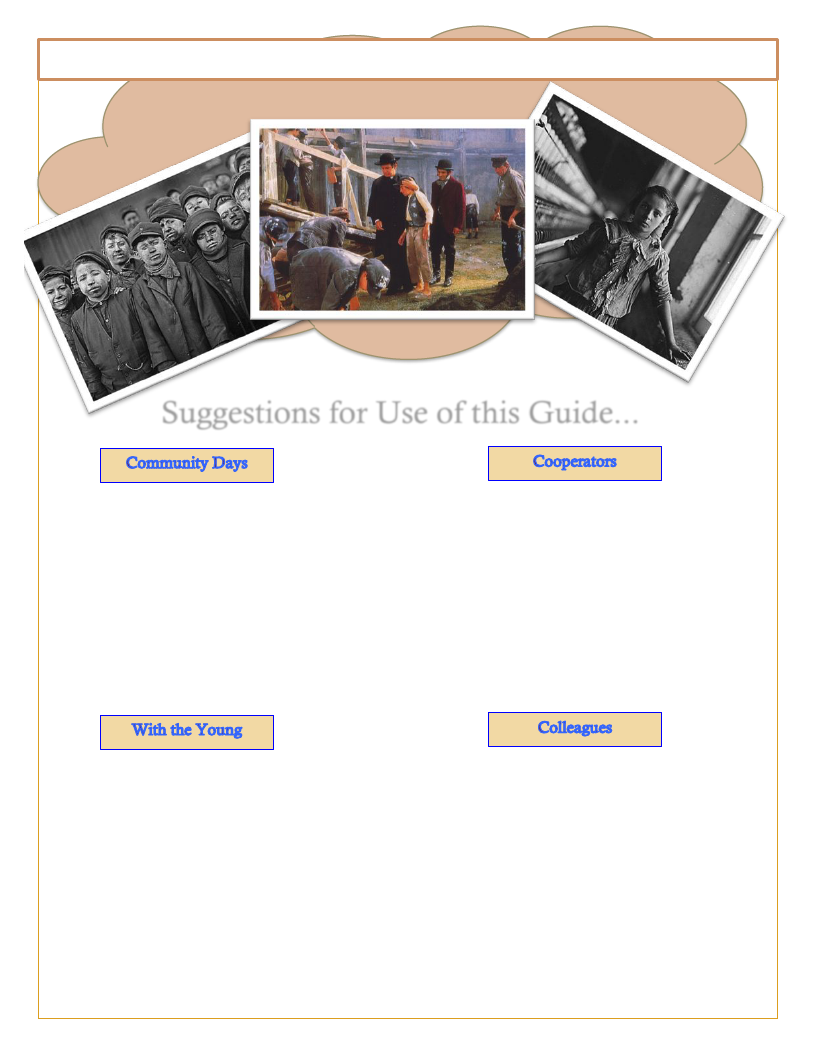

For the instruction, and as a first step in the

reformation, of such unhappy beings, the Ragged

Schools were founded. I was first attracted to the

subject, and indeed was first made conscious of their

existence, about two years ago, or more, by seeing an

advertisement in the papers dated from West Street,

Saffron Hill, stating "That a room had been opened

and supported in that wretched neighbourhood for

upwards of twelve months, where religious instruction

had been imparted to the poor", and explaining in a

few words what was meant by Ragged Schools as a

generic term, including, then, four or five similar

places of instruction. I wrote to the masters of this

particular school to make some further inquiries, and

went myself soon afterwards.

It was a hot summer night; and the air of Field

Lane and Saffron Hill was not improved by such

weather, nor were the people in those streets very

sober or honest company. Being unacquainted with

the exact locality of the school, I was fain to make

some inquiries about it. These were very jocosely

received in general; but everybody knew where it was,

and gave the right direction to it. The prevailing idea

among the loungers (the greater part of them the very

sweepings of the streets and station houses) seemed to

be, that the teachers were quixotic, and the school

upon the whole "a lark". But there was certainly a

kind of rough respect for the intention, and (as I have

said) nobody denied the school or its whereabouts, or

refused assistance in directing to it.

It consisted at that time of either two or three--

I forget which-miserable rooms, upstairs in a

miserable house. In the best of these, the pupils in

the female school were being taught to read and

write; and though there were among the number,

many wretched creatures steeped in degradation

to the lips, they were tolerably quiet, and listened

with apparent earnestness and patience to their

instructors. The appearance of this room was sad

and melancholy, of course--how could it be

otherwise!--but, on the whole, encouraging.

The close, low chamber at the back, in

which the boys were crowded, was so foul and

stifling as to be, at first, almost insupportable. But

its moral aspect was so far worse than its

physical, that this was soon forgotten. Huddled

together on a bench about the room, and shown

out by some flaring candles stuck against the

walls, were a crowd of boys, varying from mere

infants to young men; sellers of fruit, herbs,

lucifer-matches, flints; sleepers under the dry

arches of bridges; young thieves and beggars--

with nothing natural to youth about them: with

nothing frank, ingenuous, or pleasant in their

faces; low-browed, vicious, cunning, wicked;

abandoned of all help but this; speeding

downward to destruction; and UNUTTERABLY

IGNORANT.

This, Reader, was one room as full as it

could hold; but these were only grains in sample

of a Multitude that are perpetually sifting through

these schools; in sample of a Multitude who had

within them once, and perhaps have now, the

elements of men as good as you or I, and maybe

infinitely better; in sample of a Multitude among

whose doomed and sinful ranks (oh, think of this,

and think of them!) the child of any man upon

this earth, however lofty his degree, must, as by

Destiny and Fate, be found, if, at its birth, it were

consigned to such an infancy and nurture, as

these fallen creatures had!

This was the Class I saw at the Ragged

School. They could not be trusted with books;

they could only be instructed orally; they were

difficult of reduction to anything like attention,

obedience, or decent behaviour; their benighted

ignorance in reference to the Deity, or to any

social duty (how could they guess at any social

duty, being so discarded by all social teachers but

the gaoler and the hangman!) was terrible to see.

Yet, even here, and among these, something had

11