3

February Study Guide 2012

Key

Historical

Figures

(continued)

Excerpted

from

Don

Bosco

Builder,

Arthur

Lenti...

Under that reign, Cavour carried the authority of the King, but

that would end by 1848. Despite Don Bosco’s appeal to his

obedience to the archbishop, the Marquis called a meeting of his

city council at the residence of the archbishop who was rather ill

at that moment. The council decided definitively to block all of

Don Bosco’s meetings as a threat to public securtiy. This ban would

last for 6 months until Cavour fell ill. In June 1847, the city guards

were called off.1 During this illness, Don Bosco often visited the

sick Marquis and garnered favor and even financial support from the

sick man. It was during this time that Don Bosco became familiar

with his sons Camilo and Gustavo. A subsidy of more that 300 lire

came to the Oratory annually until 1877. In the following year, an

anti-clerical shift was apparent.

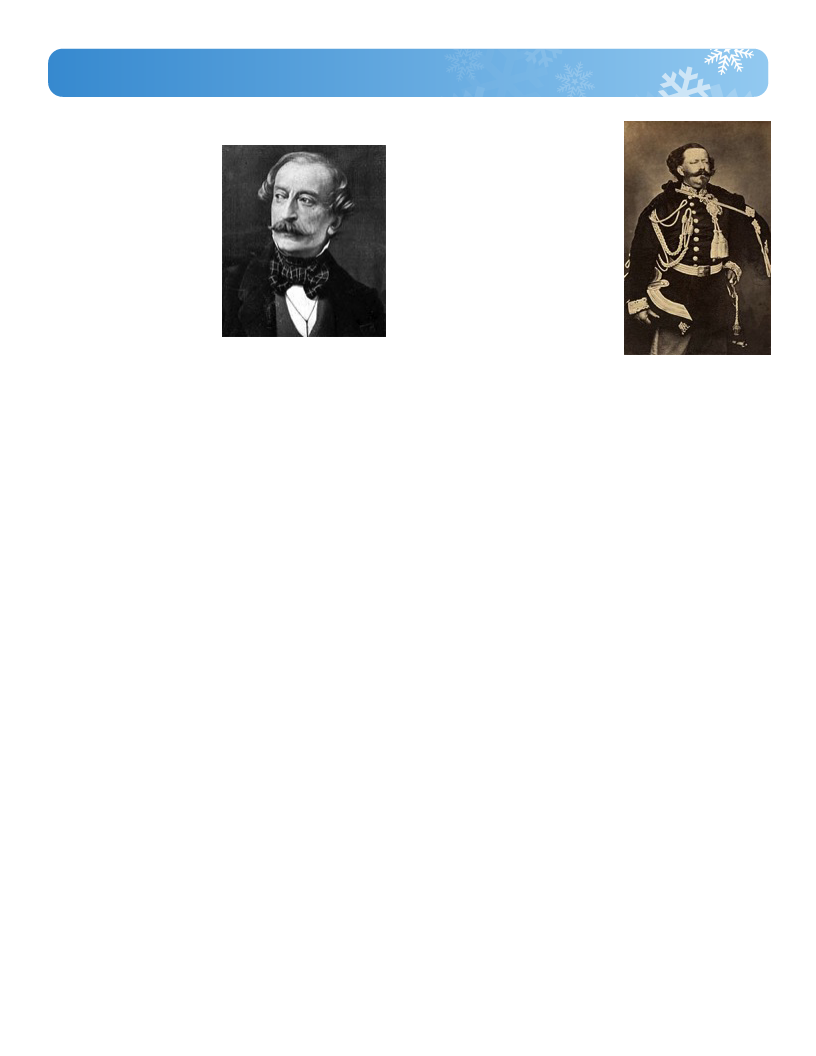

King Charles Albert

King Charles Albert clung to a throne presiding over the

region of Piedmont at a precarious interval between the Napoleanic

occupation and the anti-clerical and unifying forces of a new form of

government on the rise—a government seeking national unity and

freedom from monarchies. The king was fully aware of the growing

sentiment, especially during those years of Restoration, and did all

in his power to suppress any movement toward a constitution. A

movement that would deal the king a rattling blow began in 1831

under Giuseppe Mazzini; it was another secret movement called

“Young Italy.”1 The notes in the Memoirs of the Oratory English

translation offer many insights into the significance of such secret

societies and their impact on the life of a young clerical student,

John Bosco. It is suggested there that his founding of the Societa

dell’allegria was an innocent imitation of such groups but for vastly

different reasons.

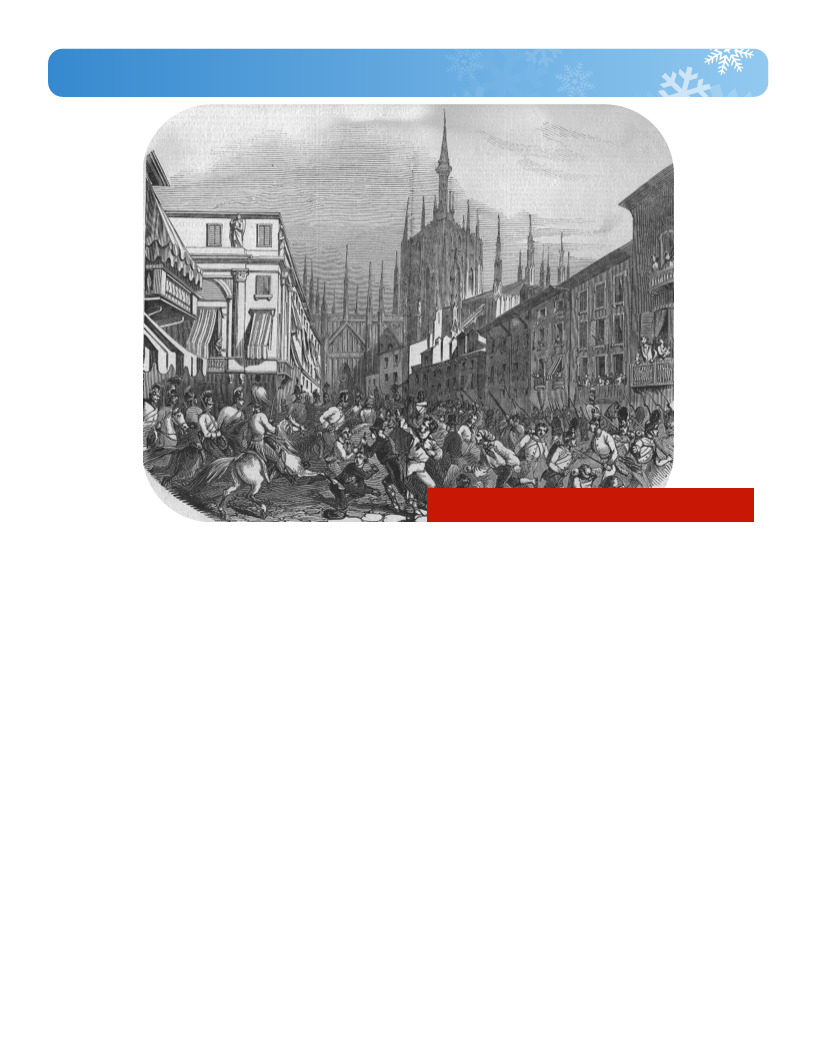

During the 1840s, King Charles Albert faced the rising

tensions between the Kingdom

of Sardinia and the Austrian

Empire.

Austria was

occupying Venice, Lombard,

and Tuscany among other

states in the northern peninsula.

A note of interest in the MO,

English Translation is the fact

that Don Bosco tolerated the

games of the boys playing with

wooden rifles, “the Italians”

versus “the Austrians.” At the

hieght of these games the

famous incident of the boys

destroying Mama Margaret’s

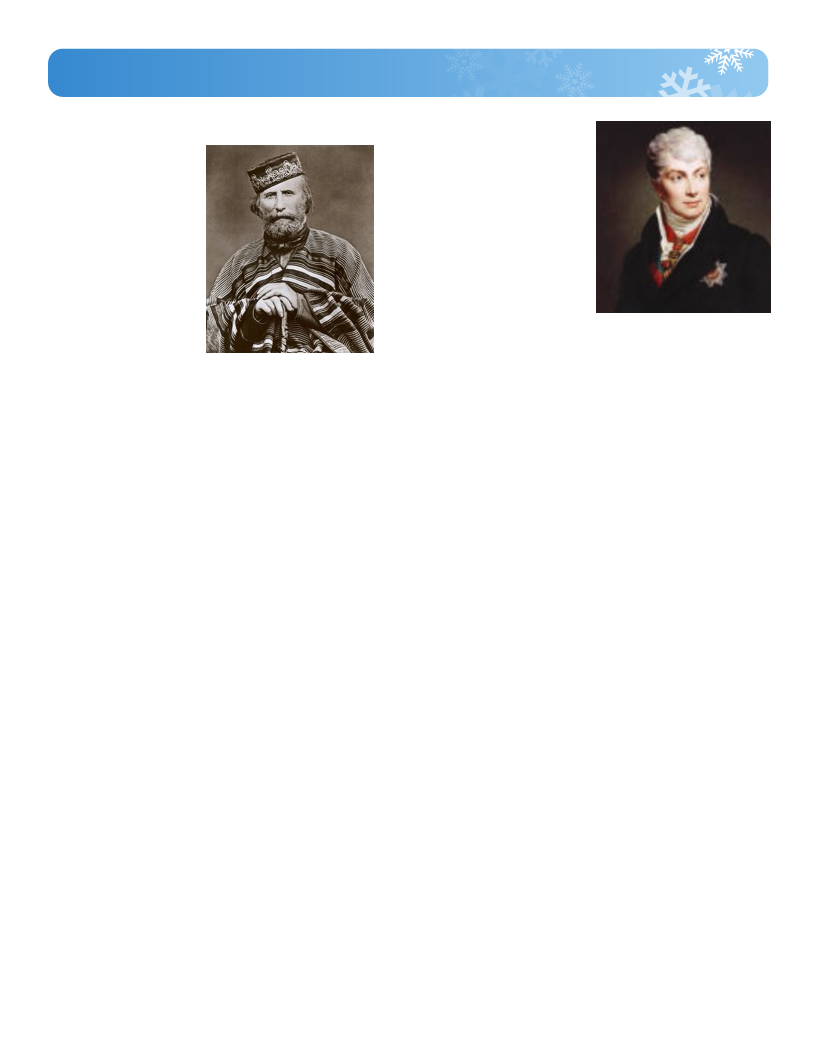

ArchBishop

Gastaldi

For

a

closing

comment,

it

bears

repeating

that,

neurotic

and

unreasoning

though

he

is

made

to

appear

in

the

Biographical

Memoirs,

Gastaldi

was

proceeding

from

clearly

defined

premises.

He

was

truly

concerned

with

clergy

reform

and

formation;

he

was

particularly

sensitive

and

protective

with

regard

to

his

own

seminary

program;

and

he

saw

Don

Bosco’s

recruiting

and

formation

practices

as

a

threat.

Add

to

this

his

unimpeachable

conviction

that

it

was

his

right

and

his

duty,

as

ordinary,

to

ascertain

the

suitability

and

worthiness

of

candidates

for

ordination,

whether

secular

or

regular.

After

all,

as

Desramaut

aptly

remarks,

Salesian

candidates

had

not

lived

in

a

closed

seminary

community;

they

did

not

reside

in

monasteries

away

from

the

world;

they

claimed

to

be

preparing

themselves

intellectually

and

spiritually

while

fully

engaged

in

activities

of

a

largely

secular

nature.

And

the

ordinary

was

being

asked

to

confer

orders

on

such

candidates

without

the

possibility

of

ascertaining

their

suitability.

Further,

he

could

not

discount

the

real

possibility

that,

once

ordained,

they

might

choose

to

return

to

the

diocese.

In

conscience,

therefore,

as

well

as

in

virtue

of

Church

law

in

force,

the

archbishop

felt

obliged

to

examine

Salesian

candidates

on

the

subject

of

their

“vocation,”

that

is,

religious

formation,

and

on

their

real

suitability

for

priestly

ministry.

Nor

did

he

wish

to

see

presented

as

Salesian

candidates

for

ordination

his

former

seminarians

who,

after

leaving

or

after

having

been

dismissed

from

the

seminary,

had

been

accepted

by

Don

Bosco.1

No

doubt,

throughout

the

distressing

developments

of

the

confrontation

that

followed,

misunderstandings,

frustration,

anger,

spite,

and

even

unworthy

motives

played

a

part.

But

the

conflict

can

be

neither

explained

nor

understood

merely

in

those

terms.

Real

issues

and

real

points

of

view

were

involved

that

had

larger

reference

than

the

character

of

the

protagonists.

5